In an era dominated by the proliferation of information through social media, the question of whether governments should require social media companies to put disclaimers on political content is an increasingly pressing concern. The move by Meta (formerly Facebook) during the COVID-19 pandemic, where disclaimers were placed on related content, offers a valuable precedent for such an approach. This strategy could potentially curtail the spread of misinformation and address the growing threat of manipulated content, particularly as AI (notably ‘deep fake’ technology) advances.

An unchecked political force

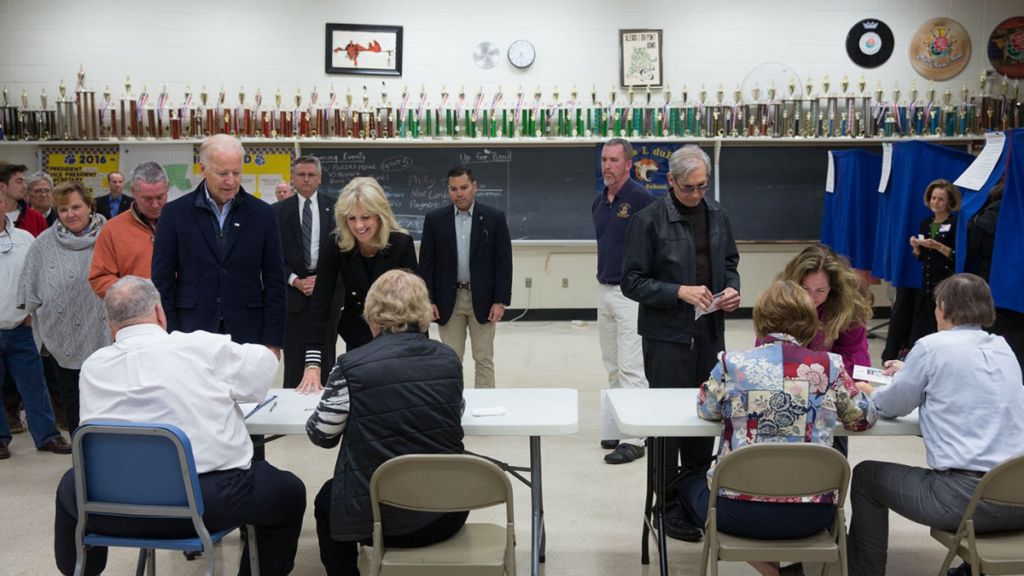

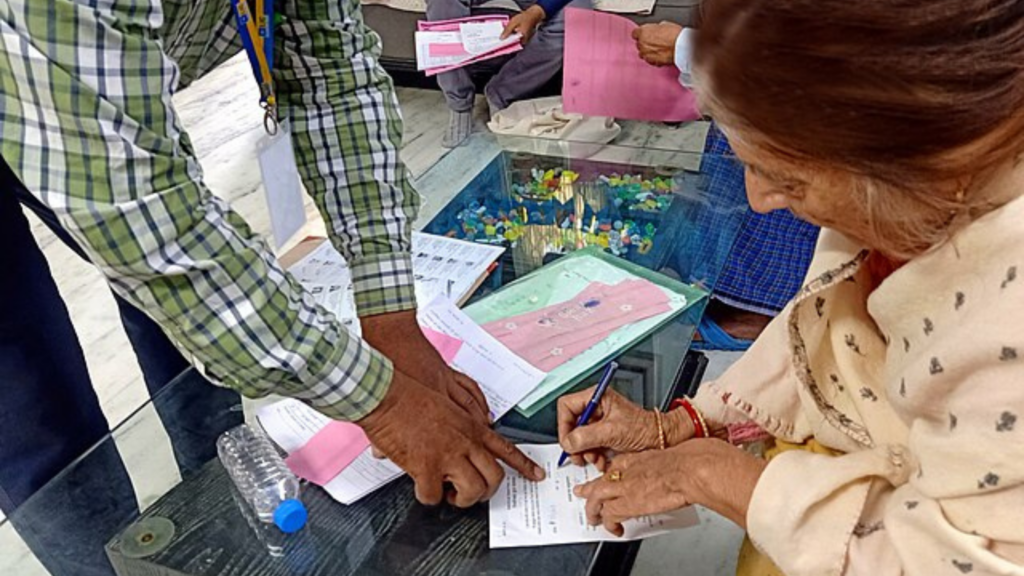

The pandemic showcased the potential dangers of the dissemination of unchecked information on social media platforms. In response, Meta implemented disclaimers on pandemic-related content to provide context and credible sources. This helped curb the spread of false information, promoting reliable sources and countering the influence of misinformation. Similarly, in the realm of politics, false or manipulated information can lead to public confusion, divisive sentiments, and can even swing election outcomes. By requiring disclaimers on political content, governments can encourage users to critically assess the credibility of the information they encounter. Possibly preventing misinformation from spreading any further and encouraging users to use their own agency and judgement to decide what information they consume.

Google recently announced that it will soon require disclaimers for AI-generated political adverts by November 2023 – no doubt seeing its potential risk at next year’s US presidential election.

AI-driven content manipulation poses a significant challenge in the modern digital landscape. Advancements in AI have made it increasingly easy to fabricate convincing content, including fabricated videos and audio recordings of public figures. Political leaders purportedly making outrageous statements can sway public opinion, creating a ripple effect that can impact election outcomes and the overall democratic process. Requiring disclaimers on political content can alert users to the potential presence of manipulated media and encourage healthy scepticism. It also underscores the responsibility that social media companies have to ensure the integrity of information circulated on their platforms. With the progression of AI technology comes bigger threats as well as possibilities to use it as a tool in managing the spread of misinformation.

Drawing parallels with France’s requirements for influencers to disclose the use of filters in paid advertisements, there’s a precedent for regulating digital content that could potentially mislead or deceive the public. Extending this concept to private users in the context of political content is a logical step. While maintaining the balance between freedom of expression and curbing misinformation is crucial, the broader societal impact of unchecked content necessitates measures to safeguard the public’s access to accurate information.

Where is the dividing line?

The question of where to draw the line between entertainment and misleading content is complex. While AI offers innovative opportunities for creativity and expression, it also presents fertile ground for the spread of falsehoods. Determining this line requires collaboration between governments, social media companies, experts in technology and communication, and civil society. A transparent and consultative approach is necessary to establish guidelines that strike the right balance between creative freedom and responsible content dissemination.

Central to this conversation is the question of who should determine where this line lies. Ideally, a multi-stakeholder approach is needed, involving government bodies, technology companies, independent fact checkers, academic institutions, and organisations within civil society. This collective effort can ensure that decisions are not made unilaterally, preventing potential biases or power imbalances from influencing content regulation. The aim should be to create a consensus-driven framework that respects both freedom of expression and the need for accurate information. One possible method would be to caveat posts with a visible disclaimer. This way social-media companies would not obstruct the freedom of creation while taking into account the importance of stopping the spread of misleading content.

The precedent set by Meta’s use of disclaimers during the COVID-19 pandemic provides a valuable lesson in the potential benefits of requiring social media companies to place disclaimers on political content. As AI technology advances, the threat of misinformation and manipulated content becomes increasingly significant, necessitating proactive measures. While striking the right balance between freedom of expression and content regulation is challenging, the stakes are high, especially in the realm of politics. Collaborative efforts involving various stakeholders can help determine where the line between entertainment and misleading content should be drawn, ensuring a healthier and more informed digital landscape for all.

The British experience

The AI technology itself should not be labelled as ‘bad’ or ‘good’. It is simply a tool in the hands of a person. The examples of that can be drawn from the real world.

For example, one notable harmful deep fake incident in UK politics involved a manipulated speech by then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson during the Brexit negotiations. In this deep fake video, Johnson appeared to announce a radical change in the Government’s stance on Brexit, causing widespread panic and market fluctuations. The deep fake was convincing enough to deceive some viewers and create confusion, highlighting the potential for deep fakes to disrupt political stability and financial markets.

Similarly, one deep fake was released in advance of the 2019 UK general election which saw a ‘fake’ Boris Johnson and ‘fake’ Jeremy Corbyn encourage voters to cast their ballot for their opponent. Whilst this would not have swayed the election, and whilst the British public ought to be afforded more credit in being able to detect malicious intent, it still poses a threat when someone’s voice is being used for the spread of misinformation.

It’s essential to differentiate between harmful deep fakes that can manipulate public opinion or damage reputations, and those designed to entertain. Vigilance and media literacy are crucial for mitigating the potential harm posed by malicious deep fakes while allowing room for creativity and humour in the digital age.