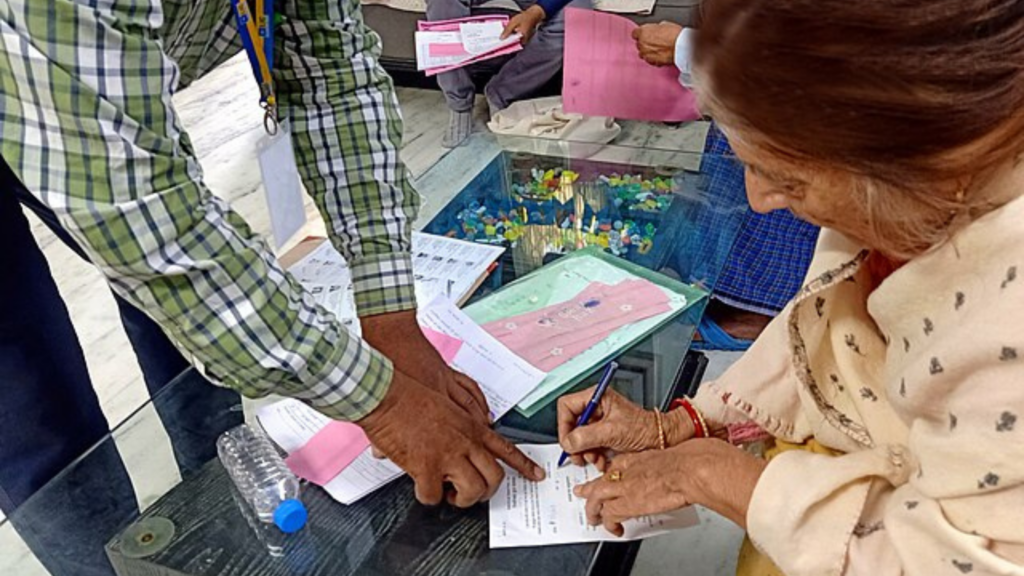

In April of last year, the UK Government passed the Elections Act 2022, which added a new requirement to the voting process: voters must present photographic identification to be able to vote. Accepted forms of ID include UK driving licenses, passports, biometric immigration documents, PASS cards issued by the National Proof of Age Standard Scheme, and Oyster cards (for those aged over 60 only).

While some believe that this policy is a step towards ensuring election integrity, others question whether it is actually a form of voter suppression, particularly given that it represents the most significant change to the voting process in 150 years.

A necessary step?

The policy was deemed necessary to increase the security and validity of UK elections due to perceived threats of voter fraud. However, according to a 2014 Electoral Commission report, there were no signs of systematic voter fraud in the UK. The report did argue, however, that the lack of a requirement to show ID at polling stations was an “actual and perceived weakness” of the UK electoral system. Despite only 193 allegations of voter fraud in 2022 (with just 1 caution being issued), this policy seems somewhat unnecessary when considering some of its potential disadvantages.

In my opinion, the implications of this policy may damage turnout in UK elections, particularly among younger voters. This is a significant concern, given that voter turnout has been declining in Europe, with the UK being one of the most affected countries.

The world is your Oyster - for some…

At face value, the list of accepted IDs already seems biased against younger voters. For example, 60+ Oyster cards are permitted while 18+ cards are not, despite both being photo IDs. This issue was raised by former Conservative Minister Lord Willets but was ultimately overturned by the Commons. Moreover, younger people are less likely to have valid photographic ID, which raises the question of whether this is a political move to alienate younger voters who tend not to vote for the Conservative Party.

Some have voiced concerns that this policy will damage overall turnout, with ex-Cabinet Minister David Davis arguing that it would “undoubtedly reduce turnout.” When a similar policy was introduced in Northern Ireland, turnout decreased by 2.3%. However, the Electoral Commission’s Pilot’s Study in 2018 concluded that no significant trend was found between having to show photo ID and a reduction in turnout. Their data found that the percentage of people not returning to polling stations after being denied a ballot for carrying an insufficient or incorrect ID did not exceed 0.7%. However, a key issue with this study is that it fails to account for all those individuals who never turned up to the polling stations due to this new legislation being a disincentive to start with. The question is not whether turnout will decrease or not, but how significant this decrease will be.

I find this conclusion particularly concerning when taking into consideration the current rates of turnout for both local and general elections in the UK. Turnout in UK elections has decreased since 1992, and given that the rate of turnout has been as low as 59% in the last two decades, policies that further threaten these figures should not be welcomed – especially with what I deem as weak justifications. However, it is important to note that supporters of this act argue that a slight decrease in turnout could be an indicator that voter fraud does exist and thus that this policy was necessary in the first place.

Some merits, few issues solved

While there is some merit in this argument, I do not believe that the Elections Act is the answer to these problems, as there are simply too many negative externalities. If the goal is to decrease voter fraud and family voting, other means of doing so should be analyzed. This is especially applicable if the Government is prepared to make drastic changes to our voting system, as we have seen with the Election Act. Furthermore, considering that the conviction rates for this crime are so low, justifying counterarguments solely on convictions may be unwise. The number of allegations since 2017 is just over 1,700 and this could be used to justify an increase of security at elections.

Moreover, the argument of family voting could also be included in this justification. Family voting remains a big issue in the electoral process, with ‘Democracy Volunteers’ recording instances of family voting in 20% of the studied polling stations. Enforcing photographic ID would tighten up security around polling stations therefore making family voting much less likely.

Considering this Act has been the biggest change in the way we vote for 150 years and it has an estimated annual enforcement cost of £18,000,000, other policy measures should have been assessed beforehand. Other policy changes such as same day registration would increase security at elections whilst not harming our political freedoms. Given that same day registration reduces the likelihood of voter fraud, it makes me wonder why this policy change has not been on the agenda for years.