The splintering of the Portuguese right: the strategic craftiness of the Liberal Initiative

On Sunday, Portugal went to the polls for its second general election in three years. Today, headlines highlight the success of Antonio Costa’s Socialist Party, which exceeded expectations and won an absolute majority. After governing Portugal for six years with the support of his more progressive partners on the left, Costa’s win this week is built on securing votes from these same former allies.

On the other side of the spectrum, the defeated leaders of the Social Democratic Party (PSD) noted that whilst left-leaning voters were able to compromise and vote tactically, the opposite happened with right-wing voters. This predicament is down partly to the failed electoral strategy of the PSD, but the success of two rising parties merits a closer look.

In the 2019 legislative elections, the Liberal Initiative (IL) and the CHEGA (Enough!) parties were both able to elect one MP, enjoying a similar 1.3% of vote. Just three years later, Chega has become the third-largest party in Portugal, with 7.15% followed by the IL, which now occupies fourth place with 4.9%.

Some reports in the international press have touched on the success of CHEGA, but less has been written about the IL, its ideas, and its recipe for success.

Who is the IL and how did it get here?

When the IL emerged officially in 2017, its founders claimed Portugal lacked a political force with a strictly liberal vision, and sought to occupy that niche. Drawing inspiration from the “Oxford Manifesto”, the IL presented a liberal social and economic agenda. For this election they developed a well-defined 600-page program, calling for a smaller state, privatisation of public services, more individual freedoms at every level, and lower taxes across the board.

The party’s radical economic proposals deviate from the more social or compassionate liberal ideas on the mainstream Portuguese right (PSD and CDS). The IL also promotes a more progressive social policy agenda, committed to tackling problems like domestic violence and crimes against sexual freedoms. A program of reduced fiscal responsibility for those with higher incomes, complemented with modern social attitudes in relation to sexuality, gender, and issues such as the use of cannabis have resonated with the urban middle classes.

The IL’s campaign found its target demographic located in cities, specifically in wealthy neighbourhoods. In Lisbon, the IL had over 10% of the vote and elected four MP’s, with over 15% in the capital’ s wealthiest parishes (Avenidas Novas, Parque das Nações, Estrela, Belém). In some of the wealthiest parishes of Porto, the IL overperformed and elected another two MP’s.

An appealing program and adequate targeting, are not enough to persuade the electorate. It was in their communication strategy that the IL excelled. One strategy was to use outdoor billboards in an innovative and humorous way. Manuel Soares de Oliveira, directing manager of Mosca (a publicity company hired by the IL), explains that due to restricted funds their strategy was to develop one or two iconic posters that could be pictured and posted online. On one occasion the IL placed a billboard of a “Monopoly” board in the centre of Lisbon (Image 1). The word Monopoly was replaced by “impostoly” (taxopoly), and the places on the board were replaced with the names of different taxes. The figure of ”Rich Uncle Pennybags” was replaced by the Socialist leader Antonio Costa. Pictures of this billboard and many others circulated online and generated thousands of shares. In four years, the IL has been able to attract more traction on social media than the socialist party – this speaks volumes about the efficacy of its communication strategy.

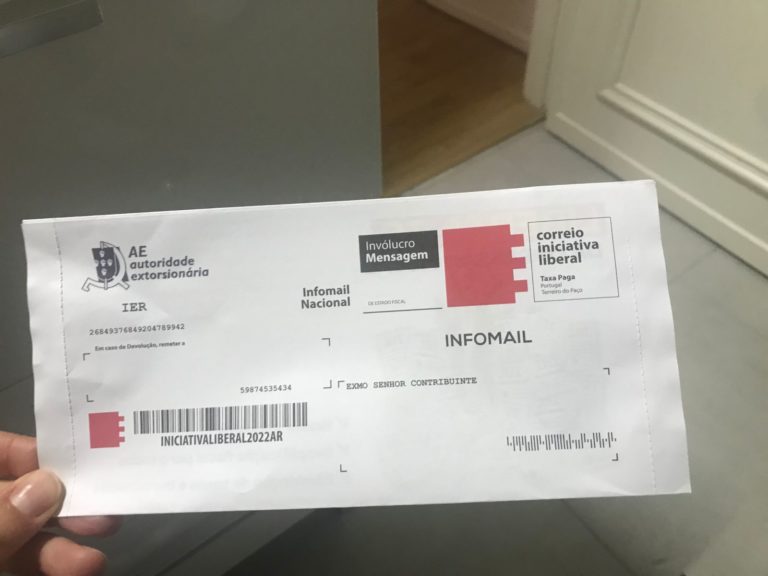

Studies conducted weeks before the election showed that about 30% of the electorate was still undecided, the IL followed the rules of political campaigning and invested heavily in campaign activity during the final week before the elections. In a creative strike, it sent flyers to voters’ mailboxes addressed to “taxpayers” resembling letters from the Portuguese fiscal authority (image 2). When voters opened the letters expecting a tax bill, each found a breakdown of how much they could save under the IL’s suggested fiscal policy. While we don’t know how much the IL’s ingenuity and unconventional marketing contributed to its electoral success, one thing we can conclude is that the IL’s creative comms and campaigning techniques allowed the party to make a credible challenge to Portugal’s established political system.