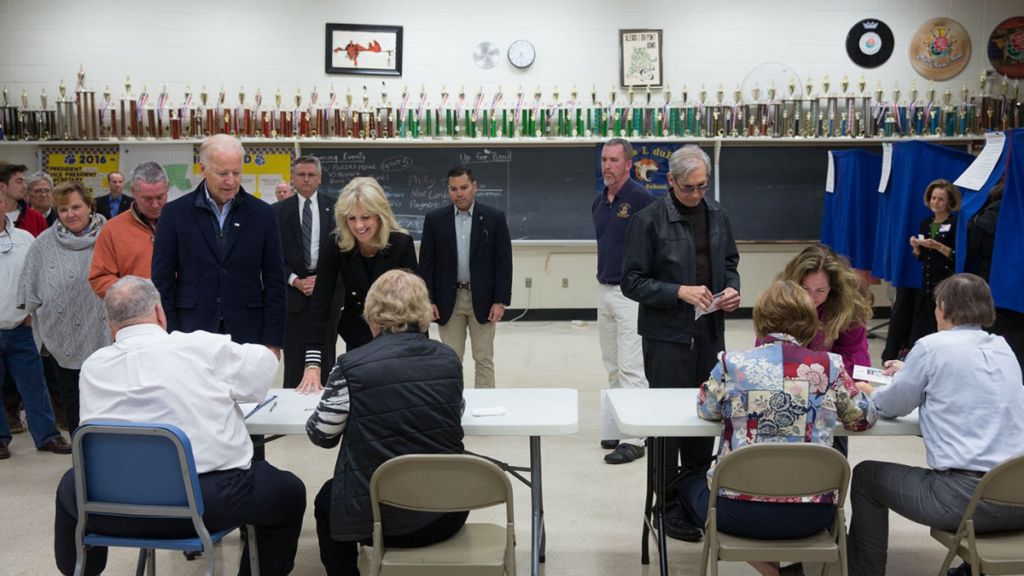

Democrats are facing increasingly brighter prospects in the last weeks and months before the all-important midterm elections. Joe Biden’s approval has improved from -20% in mid-July to -14%, but the party is now ahead of the Republicans in generic ballot polling in which people are asked which party, not candidate, they would rather vote for in the November elections.

Presidential precedent

What is notable however, is that the party seems more popular with voters than its individual elected representatives. With a -9% approval rating, the Democratic Party is more popular than Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s -20%, the party’s Senate Majority Leader, Chuck Schumer’s -16%, and Vice President, Kamala Harris’ -14%. For the first time since November 2021, more people say they would cast a vote for the party (albeit fractionally).

Democrats won 222 House seats in the 2020 election – four short of the majority threshold. According to FiveThirtyEight, Biden’s party has a 21% chance of retaining control of the House of Representatives – up from 12% in mid-July – small, but high for a governing party.

In the 19 midterm elections since the end of the Second World War, the party of the incumbent president has only once lost fewer than five seats in the House – in 1962 – and gained seats twice – in 1998 and 2002. In essence, it is very rare for the incumbent party to lose a small handful of seats, and even rarer to gain them.

Exceptional results

The relatively good performance of the president’s party in 1962 and 2002 came off the back of a ‘rally around the flag’ effect – the former being voters rewarding President Kennedy’s resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis, whilst the latter was due to the swell in support for President Bush’s response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In 1998, the political circumstances were such that President Clinton was able to win the hearts and minds of Americans who perceived his impeachment trial by House Republicans as a ‘witch hunt’.

All three were the result of very special circumstances. However, defining ‘special’ may be a task in itself. For example, an ambitious President Obama had succeeded in passing his flagship Obamacare policy and had approval in the high 40s. President George H. W. Bush had high approval following the US invasion of Kuwait and by the time of the midterm elections he had an approval rating in the low 50s. Yet both times, the President’s party lost seats in the House and Senate, the former being a historic defeat.

Will 2022 be 'special'?

2022 could be ‘special’ due to President Biden’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic – something that a narrow majority of Americans approve of. That said, just 1% of voters regard the virus as the most important issue facing the country. Maybe if the Delta and Omicron variants had never emerged, the Democrats could have successfully campaigned on them miraculously returning the USA to normality, but reality has been bumpy – epidemiologically, economically and otherwise. So whilst Coronavirus is not terribly ‘special’, its repercussions may be.

Neither should the war in Ukraine should be treated as ‘special’. Approval of Biden’s handling of the war is underwater at -16%, but voters ultimately care about how it will impact their livelihoods and how hard it will hit their pockets.

What could be stoking this revival in Democratic fortunes is the partisanship of their opponent lawmakers – this is what saw Republicans lose seats in 1998, and gain Senate seats in 2018. This year for example, the Democrats face reasonable prospects of expanding their Senate majority through states such as Pennsylvania.

Are Republicans needlessly on the offensive?

Of course, partisanship alone doesn’t guarantee an electoral backlash. Near-universal Republican opposition to Obama’s agenda didn’t hurt them at all in the midterms in 2010. Instead, what differentiated 1998 is that Republicans were on the attack and not merely trying to block Democrats from getting their own agenda implemented. In 1998, impeachment was a dramatic step and one that allowed Clinton to gain significant public sympathy. This just isn’t the case now.

This time, conservatives are exercising power not through Congress but through the courts: most importantly, through the decision by a 6-3 majority of Republican-appointed judges on the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Democrats immediately gained ground after the ruling, and in one state, Kansas, voters overwhelmingly rejected a ballot initiative that would have outlawed abortion. Moreover, Republicans have won two House races by much smaller margins than they did in the 2020 elections – in Minnesota’s 1st, and Nebraska’s 1st congressional districts. Democrats also held onto an upstate New York congressional district, widely expected to swing to the Republicans – dashing GOP hopes of a 2010-style red wave.

None of these are signs that a large ‘red wave’ is on the horizon. Republicans are also aggressively exercising power through state governments, especially on abortion, gay and transgender rights and issues, as well as education policy, and climate policy.

Enthusiasm and motivation are buoying the Democrats

Democrats are winning the motivation campaign with voters. Even though the party is reeling from decades of complacency, they now have a concrete argument that Republicans are threatening the basic rights of everyday Americans. The ‘enthusiasm gap’ often accounts for much of the presidential party’s disadvantage at the midterms, but it’s not clear it exists this year after Roe was overturned.

Ultimately, the public still views the President, his party, the economy, and the direction of the country negatively, and this is usually hard for the incumbent to overcome. Whether this election is ‘special’ or not will be dependent on what issues voters choose to vote according to – luckily for Democrats, their voters are motivated by the issues of reproductive rights, LGBT+ rights, and education and climate action. It may not be such a blue November for the party if this national political environment persists.